Guidelines for submitting articles to Roda Golf Resort Today

Hello, and thank you for choosing La Torre Today.com to publicise your organisation’s info or event.

Roda Golf Resort Today is a website set up by Murcia Today specifically for residents of the urbanisation in Southwest Murcia, providing news and information on what’s happening in the local area, which is the largest English-speaking expat area in the Region of Murcia.

When submitting text to be included on Roda Golf Resort Today, please abide by the following guidelines so we can upload your article as swiftly as possible:

Send an email to editor@spaintodayonline.com or contact@murciatoday.com

Attach the information in a Word Document or Google Doc

Include all relevant points, including:

Who is the organisation running the event?

Where is it happening?

When?

How much does it cost?

Is it necessary to book beforehand, or can people just show up on the day?

…but try not to exceed 300 words

Also attach a photo to illustrate your article, no more than 100kb

The source of the River Chícamo, a 3-kilometre walk in Abanilla

The Chícamo provides a geology lesson taking in the last ten million years!

The River Chícamo in Abanilla is one of the best known beauty spots in the landscape of Murcia, and is of special interest not only to walkers but also to naturalists and geologists. A short 3-kilometre route takes walkers back into geological history, as it features deposits left by a previous river between 7 and 10 million years ago, when what is now the north-east of Murcia was on the Mediterranean coast.

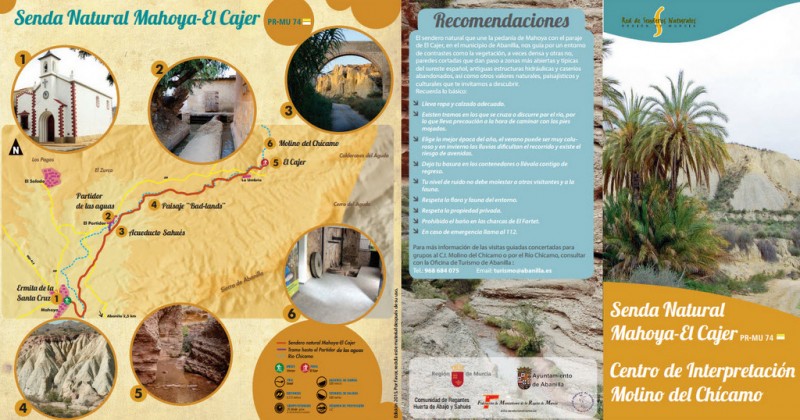

This is the first part of the PR-MU 74 . Click wikilocks

Geological history

Ten million years ago the area now occupied by the Region of Murcia was part of a strait, dotted with islands, which joined the Atlantic Ocean with the Mediterranean, and to the north of Macisvenda was a steep-sided body of land from which various streams and torrents flowed into the sea whenever it rained. These water courses left large quantities of sediment below, forming small fan-shaped delta formations.

Ten million years ago the area now occupied by the Region of Murcia was part of a strait, dotted with islands, which joined the Atlantic Ocean with the Mediterranean, and to the north of Macisvenda was a steep-sided body of land from which various streams and torrents flowed into the sea whenever it rained. These water courses left large quantities of sediment below, forming small fan-shaped delta formations.

The larger rocks and stones in this sediment accumulated close to the shore, where they underwent erosion both by the waves and by marine organisms including date mussels (Lithophaga) and demo-sponges (Clionia). Meanwhile, smaller debris was washed further into the sea and accumulated on top of seabed mud, and each solid rib of the delta was covered alternately in hardcore rocks (following periods of heavy rain) and fine sand (in times of calmer climatic conditions).

At this point in the history of the Earth the climate in Murcia was warm and coastal, with few major storms, and the sediment in the deltas was home to colonies of coral. These formed small reefs, which were occasionally buried under new waves of debris showered on them after heavy rain.

The route

The recommended route follows the course of the Chícamo downstream from its source, and begins in an area where the vegetation is dominated by palm trees, reeds and tall grasses. It is here that the river first emerges, the water flowing from various springs where it accumulates between the porous layers of rock above and the impermeable layers beneath.

This system of springs is referred to by geologists as the Chícamo aquifer sub-system: it covers an area of around 25 square kilometres, and is part of the Quibas network of aquifers (243 square kilometres).

A short distance downstream, near the Molino del Chícamo, the landscape changes and there are red Triassic rocks, clays and silicon sandstones, all of which are among the minerals still quarried in Abanilla. There are also dolomites and yesos forming a Keuper rockscape: these were formed over 200 million years ago when continental sediment was deposited into large saltwater lagoons.

Further downstream it is possible to see Tortonian formations on top of the Keuper, complete with holes created mostly by bivalve molluscs and date mussels but also by oysters and barnacles: this is visible evidence that between 10 and 7 million years ago the rock face in Abanilla was in fact the Mediterranean coast. Here the light yellow and grey layers of sediment relate to the periods of clam climate in which the ribs of the delta were covered in sand.

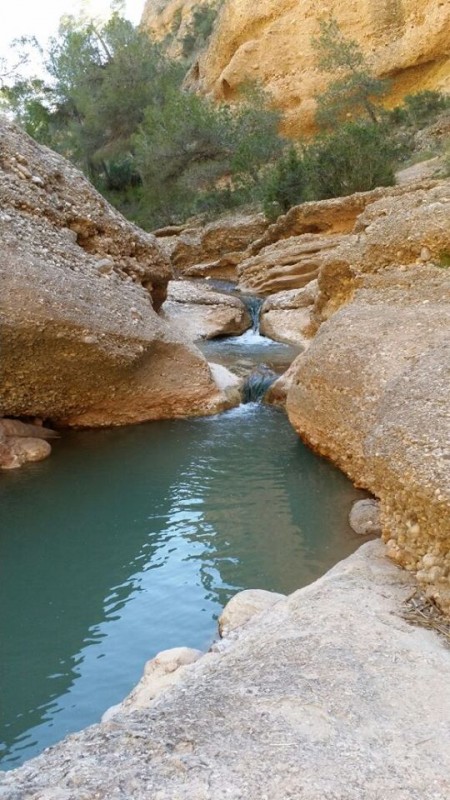

But the most iconic landscape associated with the Chícamo is a little further along the route, consisting  of a narrow gorge which has been eroded into a vast conglomerate rock formation. At some points the gorge is only two metres wide but almost 40 metres deep, and even in periods of prolonged drought there is always water in the river: on a warm day it is hard not to be tempted into taking a dip in one of the pools which form along the way!

of a narrow gorge which has been eroded into a vast conglomerate rock formation. At some points the gorge is only two metres wide but almost 40 metres deep, and even in periods of prolonged drought there is always water in the river: on a warm day it is hard not to be tempted into taking a dip in one of the pools which form along the way!

In this area it is also possible to see different layers of deposit which were left by episodes of heavy rain, some of them jutting out over the softer rock of the layer below, and the small coral reefs provide evidence of the warm coastal climate millions of years ago. These reefs did not grow to the height of those which can be seen in Fortuna (at Cortado de las Peñas) and Molina de Segura (at Comala and El Rellano) on account of them periodically being buried between fresh layers of deposit after more episodes of heavy rain.

Along this stretch of the Chícamo geologists will also spot several fault lines, some of which offered a natural advantage to the erosive force of the water as it made its way downstream. These faults are responsible for some of the 90-degree meanders in the course of the river, and at the same time walkers can see rock folds where water and calcium carbonate drip out and form travertines.

Downstream from the gorge the sedimentary rock gives way to reddish sandstone, rich in vegetable remains, and this is a sign that we are at the outer limits of the prehistoric delta formation. Slowly these in turn are replaced by yellow and grey marl formed from the seabed mud, and close to the Macisvenda road are more marl and sandstone formations which originated in swamps.

As walkers make their way back up to the road to Abanilla it is not hard for them to imagine the prehistoric landscape of ten million years ago: to the south the mountains of Abanilla, which at that time would have formed an island, to the north the Sierra del Cantón (the mainland), and in between the two a sea channel into which the delta which is now the Chícamo would have flowed, forming part of the “Sea of Fortuna”. Over time large amounts of marl were deposited into this sea before being eroded, and it was this which gave rise to the “badlands” landscape of the area.

How to reach the route

The source of the River Chícamo is close to the village of Macisvenda, and is best reached on foot from the A-9 road between Abanilla and Macisvenda: cars should be left either at the hamlet of Chícamo or in La Umbría, at the other end of the route.

La Umbria is reached from Abanilla by taking the road towards El Partidor and El Tollé, and following a signposted turning to the right after approximately 8 kilometres. Leave the car in the village and walk to the point where the road crosses the river bed.

The route itself is marked in the style of the many “PR” walks in the Region of Murcia, with white and yellow painted stripes.

Advice

- If two vehicles are available leave one in La Umbría and the other in Chícamo.

- Footwear should be selected bearing in mind that at some points the walk crosses the river, and shoes and feet will get wet!

- Where possible avoid walking on the river bed itself in order to minimize possible environmental harm.

- Refrain from leaving litter, and at all times respect native flora and fauna.

- Do not tackle this walk if heavy rain has fallen or is forecast.

- See leaflet below for full PR-MU-74 route

For further information about Abanilla, visit or contact the tourist information office or click for further information about what to see in Abanilla, for tourist information and agenda.