Guidelines for submitting articles to Roda Golf Resort Today

Hello, and thank you for choosing La Torre Today.com to publicise your organisation’s info or event.

Roda Golf Resort Today is a website set up by Murcia Today specifically for residents of the urbanisation in Southwest Murcia, providing news and information on what’s happening in the local area, which is the largest English-speaking expat area in the Region of Murcia.

When submitting text to be included on Roda Golf Resort Today, please abide by the following guidelines so we can upload your article as swiftly as possible:

Send an email to editor@spaintodayonline.com or contact@murciatoday.com

Attach the information in a Word Document or Google Doc

Include all relevant points, including:

Who is the organisation running the event?

Where is it happening?

When?

How much does it cost?

Is it necessary to book beforehand, or can people just show up on the day?

…but try not to exceed 300 words

Also attach a photo to illustrate your article, no more than 100kb

The Palmeral of Orihuela

The Palmeral is the second largest in Spain and remains the same size as during Moorish occupation

The Orihuela Palmeral, in Orihuela, Alicante province, within the Comunidad Valenciana, is the second largest artificial palm plantation in Europe behind its near neighbour in Elche, and consists mostly of date palms (Phoenix dactylifera) which are believed to have been brought here by the Moors during their occupation of Spain between 713 and 1243. ( or 1492 in the case of the Kingdom of Granada)

In the centre is a nursery area where young trees are nurtured before being used to replace older ones: the trees usually die after completing their natural lifespan of around 250 years, and some in the Palmeral are up to 300 years old.

In the centre is a nursery area where young trees are nurtured before being used to replace older ones: the trees usually die after completing their natural lifespan of around 250 years, and some in the Palmeral are up to 300 years old.

Trees belonging to other species have been cleared away and re-located in the streets of the city on order to avoid the growth of intrusive clusters of invaders within the Palmeral and restore the original structure.

It is thought that the Palmeral was first planted and exploited by the Moors after they conquered Orihuela in 713, when the pact of Tudmir relinquished control of the area from the Visigoth overlord Tudmir, to the invaders.

The Palmeral is located on the north-eastern fringe of the city centre at the foot of the Monte de San Miguel, and the western end of the Palmeral is close to the Puerta de la Olma, which used to mark the easternmost extreme of the former walled city. The old “Camino Real” (royal road) which connected Orihuela to Alicante and Valencia used to cross through the middle of the palm trees. From above it marks a distinctive green band in the landscape, a mass of square plots, dividing the land into cultivation parcels.

The Palmeral is located on the north-eastern fringe of the city centre at the foot of the Monte de San Miguel, and the western end of the Palmeral is close to the Puerta de la Olma, which used to mark the easternmost extreme of the former walled city. The old “Camino Real” (royal road) which connected Orihuela to Alicante and Valencia used to cross through the middle of the palm trees. From above it marks a distinctive green band in the landscape, a mass of square plots, dividing the land into cultivation parcels.

The trees are irrigated by the “acequias” (irrigation channels) of the Callosa de Segura and Almoradí as well as the “azarbes” of El Escorratel and Las Fuentes, and in the past there was also a spring emanating from the Monte de San Miguel. This was later turned into a spa centre in the 19th century.

The existence of these artificial “palm forests” in the Vega Baja area used to be widespread, since no special mention is made in historical documents of an area being devoted to plantations, this being a form of cultivation used extensively on the African continent.

It is estimated that there are over 130,000 date palms in the province of Alicante, with the main populations being in Elche and Orihuela. Other, smaller “palmerales” exist in Albatera, Crevillente, Redován, Callosa de Segura, Cox, Catral, Santa Pola, Granja de Rocamora, San Fulgencio and Alicante, and isolated examples occur in other towns and cities of the province.

It is estimated that there are over 130,000 date palms in the province of Alicante, with the main populations being in Elche and Orihuela. Other, smaller “palmerales” exist in Albatera, Crevillente, Redován, Callosa de Segura, Cox, Catral, Santa Pola, Granja de Rocamora, San Fulgencio and Alicante, and isolated examples occur in other towns and cities of the province.

In the larger Palmeral of Elche the growth of the city has taken land away from the palm trees, but in the case of Orihuela this has not happened, and it retains the same shape and size as when Orihuela was an Arab stronghold a thousand years ago.

That this palmeral has survived so long is due to the intense practicality of the agricultural ecosystem it created, and the fact that even when the Moors were forced out of the area, and Christian farmers moved in during the Middle Ages, the agricultural structure of the palmeral meant it could be worked just as efficiently by the new settlers, who embraced its multi layered concept.

Palmerals were the ultimate agricultural solution for hot climates in which irrigation water was available, the date palm itself offering a multitude of products, as well as yielding a valuable fruit which was an essential part of the Moorish diet.

This intensive farming scheme consisted of three different levels: at the top were the dates and palm leaves, beneath them were fruit trees bearing pomegranates, figs and other delicacies, and below these were leaf vegetables and tubers.

This multilayered structure countered the effects of the blistering sun on the plants grown at lower level, which could enjoy the warmth and dappled shade, with part of the day spent in full sun, but without the adverse effects of intense sun all day. The palms could benefit from the irrigation water given to the more tender plants below them, offering protection from the wind as well as the sun. This gave the Palmeral an important role to play in the economy of medieval Orihuela even after the departure of the Moors, yielding products which could be sold outside of the immediate areas: not only dates but also cotton, olives, mulberries, leaf vegetables and hemp. Secondary products of the palm trees themselves included baskets, brooms and palm hearts.

This multilayered structure countered the effects of the blistering sun on the plants grown at lower level, which could enjoy the warmth and dappled shade, with part of the day spent in full sun, but without the adverse effects of intense sun all day. The palms could benefit from the irrigation water given to the more tender plants below them, offering protection from the wind as well as the sun. This gave the Palmeral an important role to play in the economy of medieval Orihuela even after the departure of the Moors, yielding products which could be sold outside of the immediate areas: not only dates but also cotton, olives, mulberries, leaf vegetables and hemp. Secondary products of the palm trees themselves included baskets, brooms and palm hearts.

Even today the theoretical value of the forest is high, and a study made at the Universidad Miguel Hernández concluded that the market value of the trees contained within it is over 34 million euros. This value is due to the trees being widely appreciated for their decorative value in other parts of the world, and specimens from Orihuela were exported in the 1970s to Nice and Monaco to decorate the avenues of the two cities.

The same university is home to a special unit devoted to studying the red palm weevil, which has been destroying palm trees in southern Spain over the last few years. The larvae of the weevil eat the tree from within until it eventually collapses, and examples of infected trees were discovered in the Palmeral in 2004. The council have been engaged in a constant war with the weevil ( Picudo rojo) , using a number of biological and chemical control methods to try and limit the damage to the palmeral, also implementing a policy that for every tree destroyed, another is planted to replace it.

The same university is home to a special unit devoted to studying the red palm weevil, which has been destroying palm trees in southern Spain over the last few years. The larvae of the weevil eat the tree from within until it eventually collapses, and examples of infected trees were discovered in the Palmeral in 2004. The council have been engaged in a constant war with the weevil ( Picudo rojo) , using a number of biological and chemical control methods to try and limit the damage to the palmeral, also implementing a policy that for every tree destroyed, another is planted to replace it.

Nowadays the Town Hall of Orihuela is attempting to ensure that the whole of the Palmeral belongs to the municipality, although some small parts are still under private ownership and has slowly been acquiring remaining plots of the land. Although its economic importance is now largely a thing of the past, the idea is to make other uses of the area: already there are a large number of sports facilities among the palm trees, and the area is particularly popular with joggers and cyclists.

Although some parts of the palmeral are still cultivated, other parts have been left to lie fallow, with diverse flora and fauna having gained ground within it from the nearby farmland and mountainside. This makes it comparable in many ways with pasture land, since it makes use of traditional and sustainable techniques with ecological value. Among the flora here are indigenous species such as ironwort (Sideritis glauca) and a local knapweed (Centaurea saxicola), as well as Ibero-African plants including Periploca laevigata and Withania frutescens.

Although some parts of the palmeral are still cultivated, other parts have been left to lie fallow, with diverse flora and fauna having gained ground within it from the nearby farmland and mountainside. This makes it comparable in many ways with pasture land, since it makes use of traditional and sustainable techniques with ecological value. Among the flora here are indigenous species such as ironwort (Sideritis glauca) and a local knapweed (Centaurea saxicola), as well as Ibero-African plants including Periploca laevigata and Withania frutescens.

The Palmeral has been declared a Site of Community Importance by the European Union within the Natura 2000 network, and also enjoys the status of “Item of Cultural importance” within the Spanish heritage framework run by central government.

The date palm

No-one is certain exactly where the date palm originated, although many suspect it was in the Persian Gulf,  the Arabian Peninsula and certain parts of the Sahara. It is known that date palms were cultivated by the Egyptians over 6,000 years ago, and the dates were an important crop not only in Egypt but also in Babylon and Assyria.

the Arabian Peninsula and certain parts of the Sahara. It is known that date palms were cultivated by the Egyptians over 6,000 years ago, and the dates were an important crop not only in Egypt but also in Babylon and Assyria.

In the Iberian Peninsula the species has been present since at least the 5th century BC, having presumably been introduced by colonists from the Eastern Mediterranean, and the distinctive leaf is featured in ceramic decorations dating from this period. Many believe that it was introduced before this time, but no evidence has been found to place the assertion beyond doubt.

The Romans and Moors also knew the date palm, and the latter perfected farming and cultivation techniques which have been in use for over 1,500 years in Murcia, Alicante and parts of Andalucía.

Due to its unique morphological and physiological characteristics the tree has been widely used as a symbol: in Classical times it represented both fertility and triumph, carrying forward the traditions established by the Hebrews, Greeks and Egyptians. The Persians saw the Phoenix as a symbol for the celestial sphere, and so widespread is its symbological significance that Carl Jung identified the date palm as a symbol of “anima”, one of the two primary anthropomorphic archetypes of the unconscious mind. Even in the 21st century the motif is universal enough for it to be used in one of the world’s most celebrated land reclamation projects in Dubai!

Traditional popular legend in Spain says that the palm tree was also a symbol denoting the religious allegiance of those who lived within a house: Moors who were forced to convert to Christianity in order to stay in Spain planted a palm tree by their front door in order to mark their true allegiance.

Traditional popular legend in Spain says that the palm tree was also a symbol denoting the religious allegiance of those who lived within a house: Moors who were forced to convert to Christianity in order to stay in Spain planted a palm tree by their front door in order to mark their true allegiance.

Mentions of the date palm in stories and legends are many and various, reflecting the fact that it was cultivated throughout the Eastern Mediterranean, from the Euphrates to the Nile. Herodotus mentions the palm trees of Babylon, and in Assyrian and Egyptian monuments it is a frequent decorative motif. It appears on coins in Carthage and Mozarabic allusions to biblical themes. It was blessed by Jesus Christ and the prophet Muhammad proclaimed that “a man should be as upright, fair and generous as the palm tree”.

The date palm has always been prized for its fruit: some varieties can yield as much as 150kg per year. For some peoples around the Mediterranean the date was a part of their staple diet, and indeed in some Arabic cultures it still is.

The fruit can be matured either naturally or artificially (by impregnating it with acetic acid, generally vinegar), and in both cases it is normally consumed at room temperature. However it can also be presented as a dried fruit, cooked, as a jam preserve or in cakes, and in the Sahara date bread is used to feed the caravans travelling across the desert. The large amount of mucilaginous substances contained in the fruit make it ideal for treating respiratory problems when mixed with milk, and a highly potent alcoholic drink can be distilled from poor quality ripe fruit.

The sap of the date palm is sweet, and the Arabs drink this “lagmi” cold. “Arrack”, the liquor derived from the palm, is made by fermenting and clarifying the sap, and in parts of northern Africa the dates are believed to have stimulating and aphrodisiac properties. Furthermore, the seeds can be toasted and used as a substitute for coffee.

In parts of Spain where palms are to be found today, it is common to see the leaves of the date palm used to make “white palm” (“palma blanca”). Due to its association with the idea of triumph it is used by worshippers on Palm Sunday, before which the leaves are covered in opaque plastic which prevents sunlight from reaching them. As a result the chlorophyll is not activated and the leaves turn white, after which they are woven into complex forms and shapes. Just before Easter whole families can be seen in the streets making these beautiful palm decorations which are sold either directly outside churches or in local florists before Palm Sunday.

In parts of Spain where palms are to be found today, it is common to see the leaves of the date palm used to make “white palm” (“palma blanca”). Due to its association with the idea of triumph it is used by worshippers on Palm Sunday, before which the leaves are covered in opaque plastic which prevents sunlight from reaching them. As a result the chlorophyll is not activated and the leaves turn white, after which they are woven into complex forms and shapes. Just before Easter whole families can be seen in the streets making these beautiful palm decorations which are sold either directly outside churches or in local florists before Palm Sunday.

The practice of bleaching the leaves is known as “encapuchamiento” (or “hooding”), but has been banned in the whole of the Orihuela municipality to prevent further damage being done to the normal growth of the trees. In Elche, however, this is an important industry.

Palm hearts are also widely consumed in the south-east of Spain, particularly in the area of Orihuela, and the leaf fibres are still used today in Arabic cultures to make string, baskets and mats. Combined with camel hair they can be used as material for making tents, and at one point this use alone was enough to pay for the costs of hiring hands to look after the trees. In the towns of Albatera and Catral there is an age-old tradition of making palm brooms.

Distribution

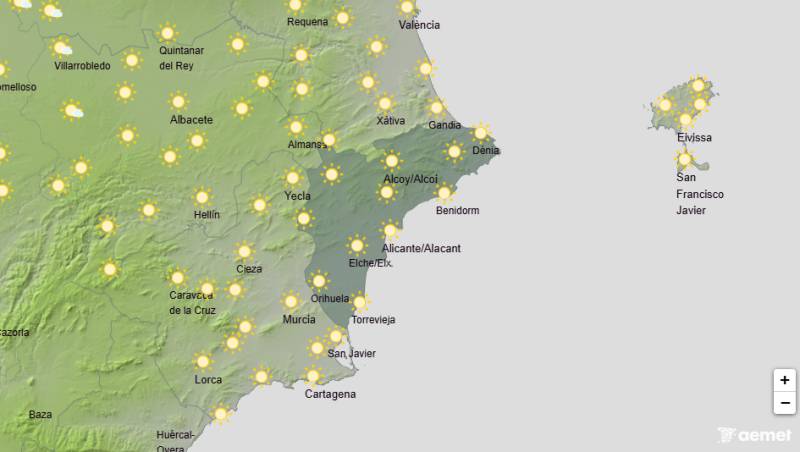

More than a dozen species make up the Phoenix genus, and Phoenix dactylifera, the date palm is mainly found in the Mediterranean basin. In Spain it is present only along the Mediterranean, from the south of the Comunitat Valenciana to the border with Portugal in the west. However the main concentration of date palms is in Alicante and the Region of Murcia, although there are also examples in the Balearics and the Canaries.

More than a dozen species make up the Phoenix genus, and Phoenix dactylifera, the date palm is mainly found in the Mediterranean basin. In Spain it is present only along the Mediterranean, from the south of the Comunitat Valenciana to the border with Portugal in the west. However the main concentration of date palms is in Alicante and the Region of Murcia, although there are also examples in the Balearics and the Canaries.

When exported to other parts of Europe the tree becomes purely ornamental, since the colder temperatures prevent the fruit from forming.

Cultivation

The Arabs were responsible for perfecting date cultivation techniques throughout southern Europe and nowadays 95% of Spain’s date cultivation takes place in the province of Alicante.

Across the globe it is believed that there must be around 80 million date palms, mainly in Asia and Africa, with the main date production centres being located in Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Algeria.

One of the most important aspects of cultivation is pruning, which is best done in July. This consists of eliminating dead and dying leaves, and at the same time clearing any remaining fruits and supporting the remaining branches. Fertilizers are used only when yields are lower than expected.

Irrigation is also important: if no rain falls this should be performed every 15 to 20 days in summer and every 30 to 40 days in winter. Watering should be avoided during flowering and harvesting, as it can cause the fruit to fall before it is ripe.